The Krust Renderer

The Renderer (Krust 2/3)

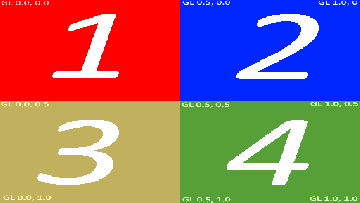

Building the renderer was the first step in creating the engine. It is a major part of the core systems and is responsible for converting sprites into quads and textures that can be drawn on the user’s screen. This is how it works:

pub fn render(...){

unsafe {gl.Clear(gl::COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);}

self.scene_manager.render(renderer);

renderer.draw();

window.gl_swap_window();

}

Firstly, the loop clears the back buffer for the next frame draw. Next, it runs the active scene’s render method in which any sprites or text that the user wishes to be drawn is added to the sprite list or text list respectively. The sprite list contains a reference to the sprite object whereas the text list contains the actual text object.

A planned development is to move the text objects into a separate class and to store a reference like with sprites. Once these lists are populated by the scene render function, the renderer calls its draw() method.

pub fn draw(&mut self){

if self.sprite_list.len() > 0 {

self.draw_sprites();

}

if self.text_list.len() > 0 {

self.draw_text();

}

self.sprite_count =

self.sprite_list.len() as u32;

//Clear lists

self.text_list.clear();

self.sprite_list.clear();

}

The draw method firstly checks if the sprite list is populated. If it is, it will call the function:

self.sprite_program.set_used();

let vao = self.sprite_renderer.get_vao();

self.bind_vertex(vao);

The shader program for sprites is bound. Next, the vertex array object (VAO) is grabbed from the sprite_renderer class. The sprite_renderer class is responsible for the vertex data (the geometry of a sprite) and all the buffers needed. These being; the vertex buffer (the buffer that holds the vertex data), the texture buffer (the buffer that stores the sprite’s image) and the model buffer (the buffer that stores the position, rotation and scale of the sprite).

Then comes the logic section. This is where the algorithm sorts the sprites into separate lists/vectors based on what sprite-sheet they are from.

let mut spritesheet_list: Vec

<Vec<&graphics::Sprite>> = Vec::new();

spritesheet_list.push(vec! {&self.sprite_list[0]});

A listing of sprite_sheet vectors is created. This is where the sprites are stored and categorized. The process starts by adding the first sprite to the first listing and then iterating through all of the sprites. With each sprite, the algorithm looks for a corresponding sprite-sheet in the current listings of sprite_sheets and find one that matches.

let mut first = true;

for sprite in self.sprite_list.iter() {

if first {

first = false;

} else {

let mut found = false;

for list in

spritesheet_list.iter_mut() {

let sheet = list[0].get_sheet();

if std::ptr::eq(

sprite.get_sheet(), sheet) {

list.push(&sprite);

found = true;

}

}

if !found {

spritesheet_list.push(

vec! {sprite}

);

}

}

}

If it finds a match, it will add it to that sprite_sheet listing. If not, it will create a new list and continue the process until all the sprites are categorised. Once categorised, it moves on to the final step.

for sheet in spritesheet_list {

sheet[0].bind();

for i in 0..sheet.len() {

let sprite = sheet[i];

let model = sprite.get_model();

let colour = sprite.get_colour();

unsafe {

... //Snippet 1

}

unsafe {

... //Snippet 2

}

self.sprite_renderer.

render_sprite();

}

}

In order to render out the sprites efficiently, they are categorised by sheet. Now the algorithm iterates through the listings of sprite_sheets and bind the texture once for each. In the above code the sheet is chosen and the first sprite is used to bind the texture into memory. Then, it iterates through the sprites in the vector of the sprite_sheet to get their model and colour data. The colour data is passed to the shader shown in Snippet 1 below.

//Snippet 1

self.gl.Uniform3f(self.gl.GetUniformLocation

(self.sprite_program.id(),self.colour_string),

colour.x, colour.y, colour.z);

In Snippet 2 the model, texture and texture coordinates are bound their respective buffers.

//Snippet 2

self.bind_buffer(

&self.gl,

self.sprite_renderer.get_tbo()

);

self.gl.BufferData(

gl::ARRAY_BUFFER,

(sprite.get_data_length() * <gl::types::GLfloat>()) as gl::types::GLsizeiptr,

sprite.get_data().as_ptr() as *const gl::types::GLvoid,

gl::STATIC_DRAW,

);

self.bind_buffer(&self.gl, 0);

self.bind_buffer(

&self.gl,

self.sprite_renderer.get_mbo()

);

self.gl.BufferData(

gl::ARRAY_BUFFER,

1 * ::std::mem::size_of::<glm::Mat4>() as gl::types::GLsizeiptr,

glm::value_ptr(&model).as_ptr() as *const gl::types::GLvoid,

gl::STATIC_DRAW,

);

self.bind_buffer(&self.gl, 0);

The texture buffer is bound and the data is set. The target is a gl::ARRAY_BUFFER, the size of the data in bytes can be worked out as the number of values (texture coordinates) in the vector of texture coordinates multiplied by the size of a GlFloat. The actual data is passed as a raw const pointer. This buffer handles where to offset the texture to correctly render the sprite’s image. It works by calculating the number of pixels along and down a texture for each vertex position called a texture coordinate.

The next buffer handles loading the model (position, rotation and scale). As before, the model buffer is bound and the target is set. For the size of the data we can just use 1 glm::Mat4 (a 4 x 4 matrix). Then, the raw pointer to the matrix is set and the usage is set to again gl::STATIC_DRAW.

Finally, the last instructions are called.

self.sprite_renderer.render_sprite();

In the sprite renderer we call the final command:

unsafe{

self.gl.DrawArrays(gl::TRIANGLE_STRIP, 0, 4);

}

This draws our vertices and these vertices have the desired position, rotation and scale in the world with the correct texture applied to them.

![]()

For rendering text, the system works very much the same as with sprites. Text is added to the text_list and drawn at the end of the loop. Text can be altered by giving it a position, scale and colour. One of the major limitations of the current system is the font loading system. The engine can only currently use one font which is going to fixed in future. In order to load in fonts the engine uses a library called freetype.

for c in 0..128 {

//Load characters glyphs

freetype::FT_Load_Char(

face, c as u32,

freetype::FT_LOAD_RENDER as i32

);

let bitmap = (*(*face).glyph).bitmap;

let texture = generate_texture(

gl, bitmap

);

let character = Character {

texture,

size: glm::vec2(bitmap.width as i32,

bitmap.rows as i32),

bearing: glm::vec2((*(*face).glyph)

.bitmap_left,

(*(*face).glyph).bitmap_top),

advance: ((*(*face).glyph)

.advance.x) as u32

};

characters.insert(

c as gl::types::GLchar, character

);

}

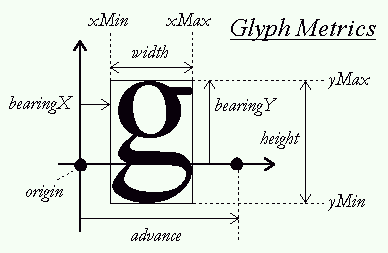

In the above code is a ‘for loop’ that uses FreeType to load in the texture for the provided font and character. The texture is then assigned to the specific character along with with the size, bearing and advance as seen in the glyph.

Next, for each of the characters the vertex data needs to be bound. This process is done when rendering by:

for c in text.chars() {

let ch = &self.characters[&(c as i8)];

let x_pos: f32 = offset +

position.x +

(ch.bearing.x as f32) *

scale;

let y_pos: f32 = position.y +

((ch.size.y - ch.bearing.y) as f32)*

scale;

let w: f32 = (ch.size.x) as f32 * scale;

let h: f32 = (ch.size.y) as f32 * scale;

let vertices: Vec<gl::types::GLfloat> =

vec!{

// Pos // Tex

x_pos, y_pos - h, 0.0, 0.0,

x_pos, y_pos, 0.0, 1.0,

x_pos + w, y_pos, 1.0, 1.0,

x_pos, y_pos - h, 0.0, 0.0,

x_pos + w, y_pos, 1.0, 1.0,

x_pos + w, y_pos - h, 1.0, 0.0

};

unsafe {

... //Buffer Bind and Render

}

}

A string is converted into a character and this character is used to lookup the relevant glyph inside of the characters array. The 4 coordinates are determined using the previously mentioned variables. Additionally, the scale can be applied at this stage. The texture coordinates are also bound in the same vertex array. Once all the characters of a string are bound it can be rendered to the screen.

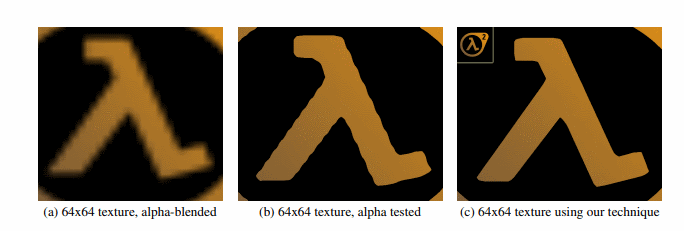

Scaling the text can present a problem due to the text’s fixed size. If the text is stretched across the entire screen you can start to notice blurriness or low-quality textures for the characters depending if anti-aliasing is being used. This is where signed distance fields can be used to create clear text at most resolutions. In the paper by Chris Green he details the process of using signed text fields to improve text quality.

Instead of storing the fonts as a bitmap texture it functions by storing the distance from each texture pixel to the edge of the character and uses a shader to compute the hard edges. This allows the engine to render text at any resolution while only needing to use a small texture for the font saving on GPU memory.

This video demonstrates this effect in action. The engine does not currently enable this functionality. Instead, other systems were prioritized but, this is a definite planned feature which has had research put into it.

References

Green, C. (2007). Improved alpha-tested magnification for vector textures and special effects. ACM SIGGRAPH 2007 Courses on - SIGGRAPH 07. doi:10.1145/1281500.1281665